CAUTION: PLEASE PARK CAREFULLY AND DO NOT BLOCK ACCESS TO PROPERTY. TRAFFIC THROUGH CARHAM CAN BE VERY BUSY SO PLEASE TAKE EXTRA CARE WHEN CROSSING THE ROAD.

Introduction

As you can see, today Carham is a very small hamlet comprising of a farm yard and a few houses and cottages.

But Carham hides her history well.

- The road through the village is ancient, perhaps of Roman origin.

- From the seventh century Carham has been the site of religious establishments.

- Over the years Carham has seen battles and the passing of armies.

- William Wallace camped here site on his way to Battle of Dunbar

- and, for one thousand years, Carham has held a sometimes precarious place on the Border between England and Scotland

Today the village of Wark is much larger than Carham, but Wark’s history is transient in comparison to its smaller neighbour, but it does have a major part to play in the turbulent history of the Border.

1. Phone Box

The red phone box was bought from BT by Carham Parish Council to be used as a “Very Small Visitor Centre”, a twin for the similar “Flodden Visitor Centre” in Branxton.

Obviously space is very limited, but there are several display panels inside, the largest being a map showing the sites of fifty conflicts between England and Scotland.

These took place over a period of some five hundred years from Carham in 1018 to the last major battle of Flodden in 1513. It can be seen that there is a distinct concentration of conflicts on both sides of the River Tweed in this eastern Border area.

There are other smaller information panels including : the rulers of England and Scotland, dates of events in Carham’s history and the East /West divide of Old English and Cumbric languages.

2. Carham Church

There is a more substantial display in the Parish Church of Saint Cuthbert.

Six explanatory display boards explain:

- The history of the Church in Carham dating back to the seventh century origins of Saint Cuthbert’s Minster, through the Augustinian Priory to the various versions of the Parish Church.

- A brief history of Saint Cuthbert.

- An explanation of how the ancient Kingdom of Northumbria was attacked from the North, South and West and was reduced in size finally to become the County of Northumberland.

- A map showing an interpretation of the battle of 1018.

- An explanation of weapons and battle tactics.

- The legacy of 1018 and Carham’s place on the Border.

A later addition is a board explaining the recent archaeology project. It shows the topography in great detail and evidence of the Henry I’s Augustinian Priory, and the 7th century Cuthbert Minster.

It demonstrates how the Cuthbert influence in Carham might have determined the rather odd line of the Border near here.

The board marks a now disused ford across the Tweed which links to an ancient track, probably a drove road, from Birgham on the north bank of the river and also to Shidlaw Lane and the South.

It is known that a Roman road ran close to Carham and this along with the ford and drove road would have made Carham a place of significant for military, ecclesiastic, and other travellers

3. Board and River

Behind the church there is an information board showing the Border along the River Tweed, and the concentration of conflicts in this area.

It also depicts the line of early Norman defensive castles, and many of the rash of towers that were built in later years as refuge from Reiving raids.

For five hundred years this was a warlike and troubled land.

At Carham the River Tweed has moved over the centuries, but today the distance North, South and West from this point to the Border is marked, The Border

The northern border of Northumbria at one time lay on the Firth of Forth, but the Battle of Carham in 1018 moved the eastern end of the Border to the line of the River Tweed which became the de facto Border after the Battle, but not the formal de jure Border until the Treaty of York in 1237.

From this point the Border between England and Scotland is approximately 500 yards due North, 80 to the West and perhaps surprisingly 1 mile to the South and then a further 15 miles before again reaching England.

This accentuates Carham ‘s remarkable position at the very edge of two nations.

Since ancient times a river crossing has existed here, and the Tweed is still fordable in summer low water.

Many invading armies, both North and South, have crossed here and this became a convenient place for conferences of war and of peace and also Border Courts.

This is not simply a North / South, but also an East /West border with the Cumbric / Welsh culture and language to the West creating a more significant divide than the Old English speaking population who were dominant from Humber to the Forth.

4 Event Field

The field directly to the East of the Church and village is where the 1000th anniversary re-enactment event was held.

Although there is no written or archaeological evidence, this is the most likely site for the battle of 1018.

Reasons for this are as follows:

- The presence of St Cuthbert’s Minster would make this an attractive target for attack, but most definitely a place worth defending.

- The road through Carham is of ancient, probably Roman origin, and provided good access for the defenders.

- There was a river crossing here – many early battles were fought at river crossings.

The Battle, weapons and tactics

Early medieval armies were small with combatants numbering hundreds rather than thousands and armies travelled light, living by forage and plunder.

Weapons were similar on both sides, consisting of bow, javelin and spear and sword and axe for hand to hand fighting. Body armour consisted of chain mail and steel helmet.

The main battle formation was the shield wall, with the two walls facing each other.

Arrows, then javelins started the fight as the walls approached each other before the close order carnage decided who was the stronger. Battle was decided when a shield wall was broken, or outflanked, either by shear strength or force of numbers.

Warriors were very valuable commodity and casualties were kept to an absolute minimum and flight from carnage was the usual option for the defeated army.

Here three armies were involved: the attackers a combined force of Scots from the North commanded by King Malcolm II, and Strathclyde Cumbrians commanded by Owen the Bald, King of Strathclyde.

The defenders were the Northumbrians under the command of the Earl of Bamburgh.

The battle itself would have been short, vicious and bloody.

The battle formation of the day was the shield wall; each side would form a line, three or more ranks deep facing each other.

First insults were shouted, then missiles hurled, before face to face, hand to hand combat with spear and sword became brutal reality. The wall that broke lost the battle and in this case it was the Northumbrians The result, probably decided within a couple of hours, was victory for the attackers, and the land north of the Tweed became forever part of the emerging nation of Scotland.

Drive to the layby on the right hand side of the road just before Wark village. From here the site of Wark Castle can be seen almost dead ahead.

5 Wark Castle From Road

Wark Castle is often thought to be a marker for the battle, but construction was not started until 1136 and is therefore not significant to the conflict.

Forming part of the defensive line of castles along the Tweed, the castle was built during the early years following the Norman Conquest. The castle walls enclosed almost all the present day village (which includes a large area between the road and the River Tweed which cannot be seen from the main road)

Wark was attacked and taken by the Scots on several occasions, with a 1370 skirmish marked on OS map. The Castle was severely damaged during James IV’s Flodden campaign, and was finally abandoned in 1549. Legend has it that this was here that the Order of the Garter originated.

Today Wark is a much larger village than Carham, but has no church, shops or public building. Its original purpose was to service the castle.

Less than a mile to the West of the Castle is Gallows Hill, a grim reminder of the fate of several invading Scots.

The Border and The Border Glitch

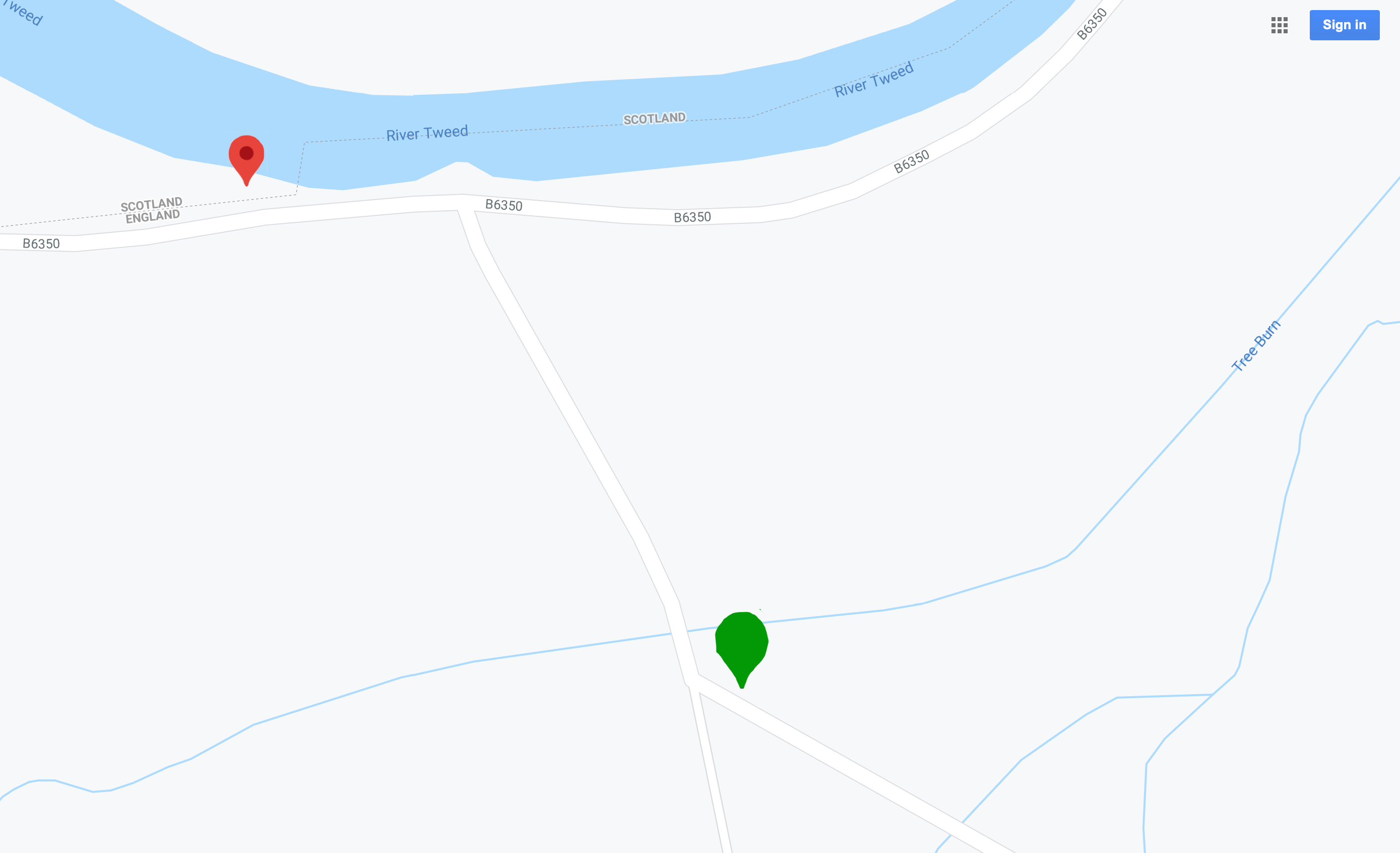

Just over a mile to the east of Wark village the River Tweed runs very close to (and sometimes over!!) the road. Although this is an area known as Dry Tweed, it still floods when the Tweed runs high after heavy rain (see green pin on map above).

This is thought by some to be the likely site of the Battle of Carham. Evidence for this is the proximity of Wark Castle and the battle site being marked here on some earlier editions of OS maps.

But this does not hold up because the Castle was not built until one hundred years after the battle, and the OS markings are irregular and sporadic.

There is conclusive evidence that, over the centuries, the Tweed has changed its course, and one thousand years ago it ran about four hundred yards further to the south and, what is now a flood plain, was marshland and, even if not in the river itself, entirely unsuitable for battle.

For one thousand years the eastern Border between England and Scotland has followed the course of the Tweed as far upstream as Carham.

The only major exception has involved the town of Berwick which has changed hands many times and for many different reasons. Berwick has been fought over and on occasions fallen both England and Scotland; it has been sold, bought back, given away, and not always by those who had the authority so to do.

There is another Border glitch (see red pin on map above) immediately to the west of the road junction where the field on the southern side of the Tweed is actually in Scotland.

This is the result of the change in the course of the river, but several folklore tales have arisen over the years suggesting different reasons for this anomaly.

The England Scotland Border

The Border along the Tweed from Berwick to Carham was in effect settled by the Battle of Carham in 1018, but this was not fixed in law until the Treaty of York in 1237.

Just to the West of Carham, for nearly thirty miles, the Border runs to the south and the east, over moorland and mountain, until it regains its westerly course to reach the coast at the Solway Firth.

In no place does the Border touch Hadrian’s Wall. The rather odd dogleg is perhaps an echo of the1018 battle when two armies, one from the North and one from the West came to fight at Carham.

Two of the earliest Border castles along the Tweed can be found:

At Norham on the south side of the Tweed - The earliest remains of the original Scottish castle at Berwick on the north side of the Tweed.

Near the village of Branxton - marking five hundred years of Border conflict, the Flodden Battlefield Trail marks where the last major battle between England and Scotland was fought in 1513

Further Information

Much more detailed information can be found on the Carham 1018 Society's website. Please see: http://carham1018.org.uk